By film critic and creative director Takashi Shimizu

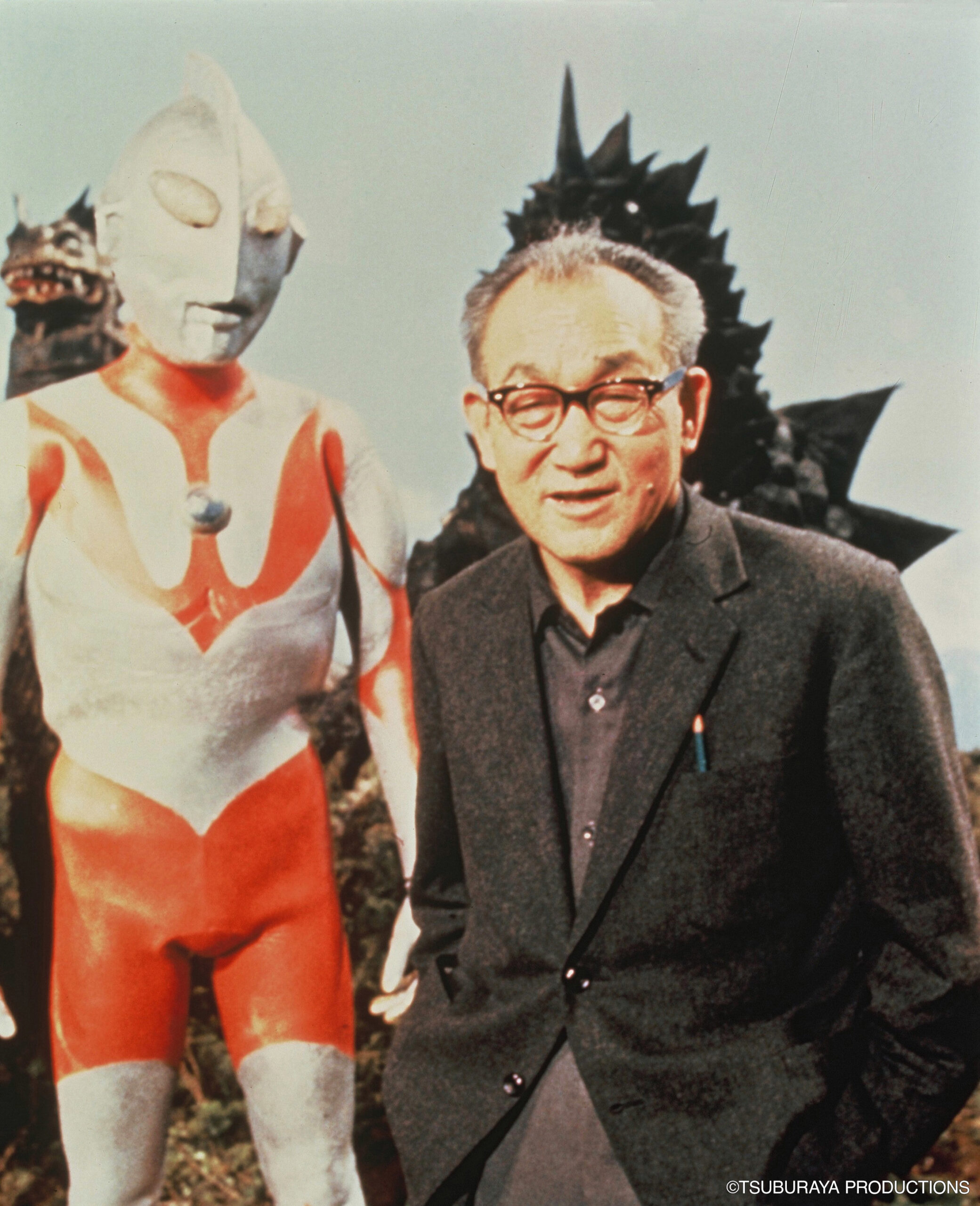

As the 60th anniversary of the first broadcast of the original Ultraman approaches, founder of the fantasy tokusatsu series and “Father of Tokusatsu” Eiji Tsuburaya (1901-1970) earns a place in the internationally renowned professional organization VES (Visual Effects Society)’ Hall of Fame. Tsuburaya is the first Japanese creator to be bestowed this honor.

Founded in 1997, VES has over 5000 members working in the movie, television, anime and gaming VFX industries, primarily in Hollywood. Every year VES contributes to the development of the industry by bestowing an award often known as “the Academy Award of the VFX world” upon innovative creators and their works. The names of those who have made great achievements throughout their lives will be immortalized with the special honor that is the “Hall of Fame” status.

Who is in the Lineup of the VES Hall of Fame Legends?

To date, around 60 legends have had their names immortalized in the Hall of Fame, and these are not limited to widely known producers and directors such as Walt Disney, Stanley Kubrick, and Stan Lee. The list also includes The Lumière brothers, who developed the cinematograph- a device used for filming, developing and projecting- which many would agree was the beginning of cinema. Soon after the birth of cinema, Georges Méliès discovered special effects, and became the pioneer of SF and fantasy movies with his 1902 movie Le Voyage dans la Lune. Developer of 3DCG rendering software RenderMan, Pixar founder and Disney animation studio leader Edwin Catmull. John Knoll, who co-developed image editing software Photoshop with his brother, as well as working as a VFX supervisor at ILM (Star Wars series). On top of the above, the list also includes Willis O’Brien, George Pal, Irwin Allen, Ray Harryhausen, Gene Roddenberry, Derek Meddings, Douglas Trumbull, Dennis Muren, Phil Tippett, Syd Mead… A lineup of creators that is sure to spark excitement into the heart of any SFX or SF fan.

It is a great achievement for Japan to be able to stand side by side with the American and European masters, whose advances in VFX have helped to shape the history of cinema. Eiji, who served as special effects director for the Godzilla series, as well as being the father of the Ultraman series, had been a hot topic worldwide for some time, but surely being the one to show the world special effects of a giant hero and kaijus isn’t the only reason he joined the Hall of Fame. What about his cinematic accomplishments up until the mid-20th century? Let’s examine.

The Early Days of Western Cinematic Technique and Knowledge

A key point in Eiji’s life was taking an interest in the West’s superior technology. Eiji had enjoyed tinkering with machines since his youth, and was inspired by the at-the-time new invention of the airplane. Although he gave up on his dream of becoming a pilot, he set his sights on another modern marvel: the world of cinema. In the golden age of silent cinema, films using elementary special effects such as stop trick, double exposure, and reverse rotation were thriving, but cinema failed to gain momentum on the cultural, artistic or technical side. At that time, an 18-year-old Eiji was apprenticing under Yoshiro Edamasa, a director and cinematographer who, determined to reach a level of cinematic technique that rivalled that of the West, had gone to America to study. His spirit would go on to be a compass for his cinematic career.

Arming himself with various technical skills, he began his career as a camera assistant, and in 1923 he finally became an independent cameraman. In his mid-twenties he worked as assistant on director Teinosuke Kinugasa’s film, A Page of Madness (1926), which helped him to grow. Taking inspiration from German expressionism, Eiji emphasized shadows in order to paint a picture of human insecurity and insanity. Making use of multiple exposure and flashbacks, he was able to create an avant-garde film. Eiji invented the pan transition, an innovative camerawork technique which involves moving the camera to the side to connect to the next scene. With the discovery of such camerawork techniques, he developed a sense for elevating technique to expression.

At the beginning of the 30’s, the Hollywood movie King Kong (1933) took the world by storm. Using stop motion animation, they were able to breathe life into the beast, and through the elaborate composition of this with the humans they were able to give a sense of the sheer size of the monster, surprising and impressing viewers. Eiji got hold of prints of the frames and carefully analyzed them one at a time. The film’s special effects were supposed to be kept behind the scenes, but Eiji recognized that the more impressive the technique, the more captivated the audience would be.

From Admirer of Western Techniques to Japanese Cinematic Revolutionary

As Eiji resisted the idea that the only important thing is that an actor looks attractive on screen, he went against upper management and would shoot in a low-key tone that emphasized reality, eventually quitting the company. He spared no time in using his own money to get to work on developing new techniques until finally someone who supported him appeared. A trading company that imported American machinery and German film founded J.O. Studios with the philosophy of innovation in film. Eiji was appointed chief cameraman. They made Japan’s first iron shooting crane, making elegant movement possible during filming, used in films such as the musical, Princess Kaguya (1935).

Then, the screen process (synthesizer) that they had been researching and developing for some time finally came to fruition. In the German co-produced film, The Daughter of the Samurai (1937), a screen was placed behind the actors, and a background was projected behind them, allowing the acting and background to be filmed at the same time. This was known as rear projection. This effective equipment built by Eiji alone allowed scenes to be completed on set, reducing the amount of labor on location shoots. The director Arnold Fanck, who upon seeing the completed movie, was said to have praised the equipment as being even better than European equipment. With these results, Eiji reached a turning point.

In 1937, J.O. Studios merged with 3 other companies to found Toho, where Eiji was invited to be head of the special effects department. The head of Toho, Iwao Mori, who was familiar with the Hollywood production industry, insisted on the importance of special effects in the film industry and paid special attention to Eiji’s work. As the war began, special effects war movies were popular. In The War at Sea from Hawaii to Malaya (1942), Eiji created a vast open set and shot with large-scale miniature models to reproduce realistic attack scenes. At the time, those scenes would have been impossible to express without filming mid-battle, but after returning home at the end of the war, the GHQ said that the quality was so high that it was believable as real footage.

After the war, Eiji’s next work to shock the public was Godzilla (1954). Due to Japanese film production time and budget, Godzilla was unable to be shot in Kong-like stop motion animation style, so they instead had an actor wear a kaiju suit and filmed him in slow motion, giving the film a heavy, ominous feel. The world-renowned work tells the tale of a giant monster born from radiation destroying a civilized society, reminding viewers of the war and clinging to prayers for peace. The movie demonstrates a sense of imagination that could only be expressed in movies.

Inheriting the “Power of Imagination” left behind by Eiji Tsuburaya

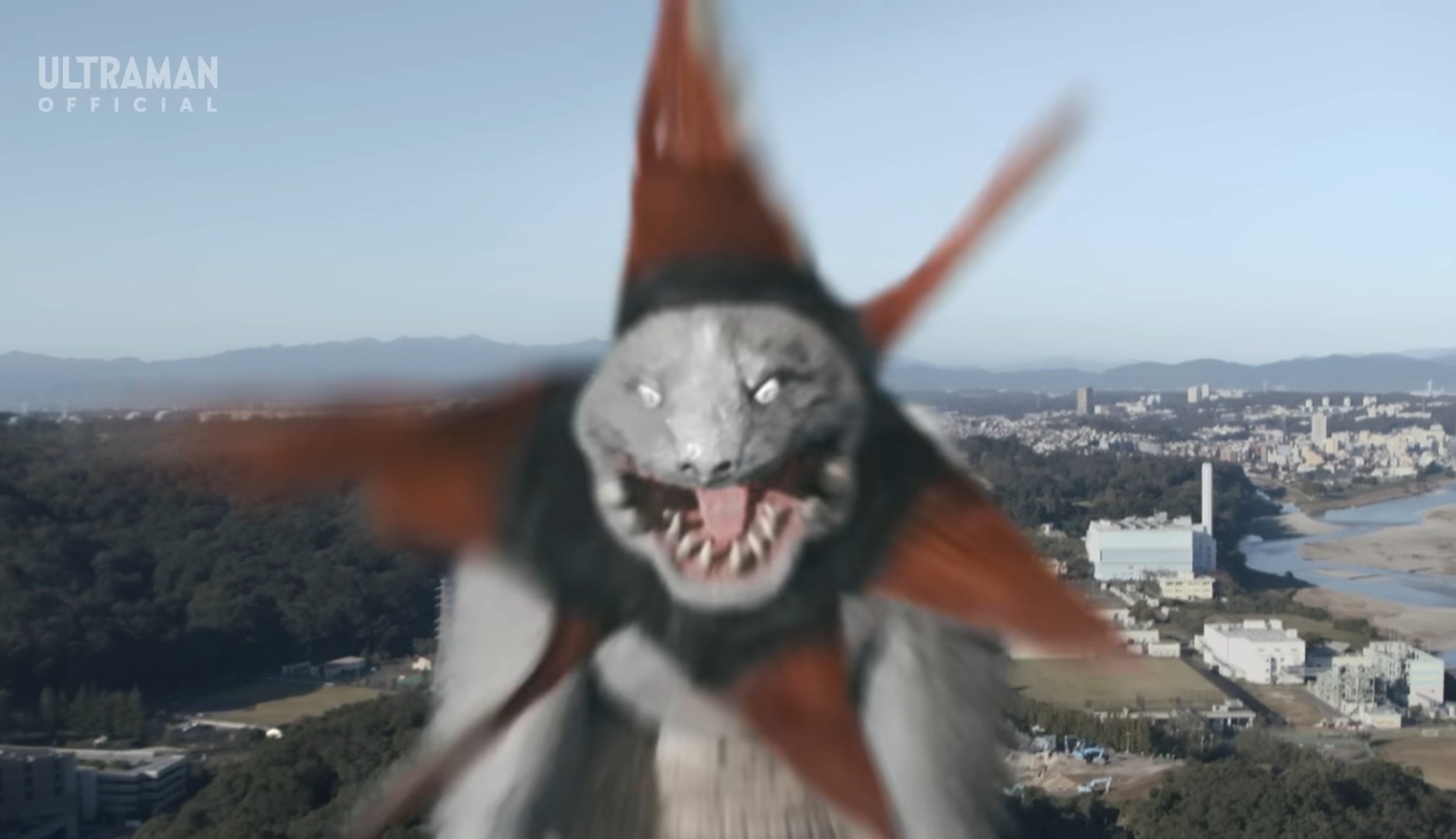

From the 1950s to the 1960s Eiji worked on numerous kaiju, SF, and fantasy films. With various tools to create high levels of surprise and realism, tokusatsu became a big genre in Japanese film. Eiji was not satisfied with this. “I am not satisfied with being remembered for kaiju movies alone,” he has been quoted as saying. “Artists use brushes to paint pictures, but filmmakers use their skills to paint dreams.” This was his philosophy on filmmaking, and to Eiji, special effects were at the most cutting-edge of cinematographic techniques.

Soon after the release of the smash hit King Kong vs Godzilla (1962), Eiji toured the West to observe their film studios. This was during a period where most filmmakers weren’t paying attention to up-and-coming media and television. However, Eiji was confident that he had a chance, as he had noticed that Hollywood was becoming more active as it took over the production of television dramas. In April of 1963, half a year after having returned to Japan, he founded his own production company, Tsuburaya Special Effects Production (soon to be changed to Tsuburaya Productions). Then in his 60s, Eiji took on the challenge of planning and producing a TV show himself; the fantasy tokusatsu series Ultra Q (1966) and Ultraman (1966-67).

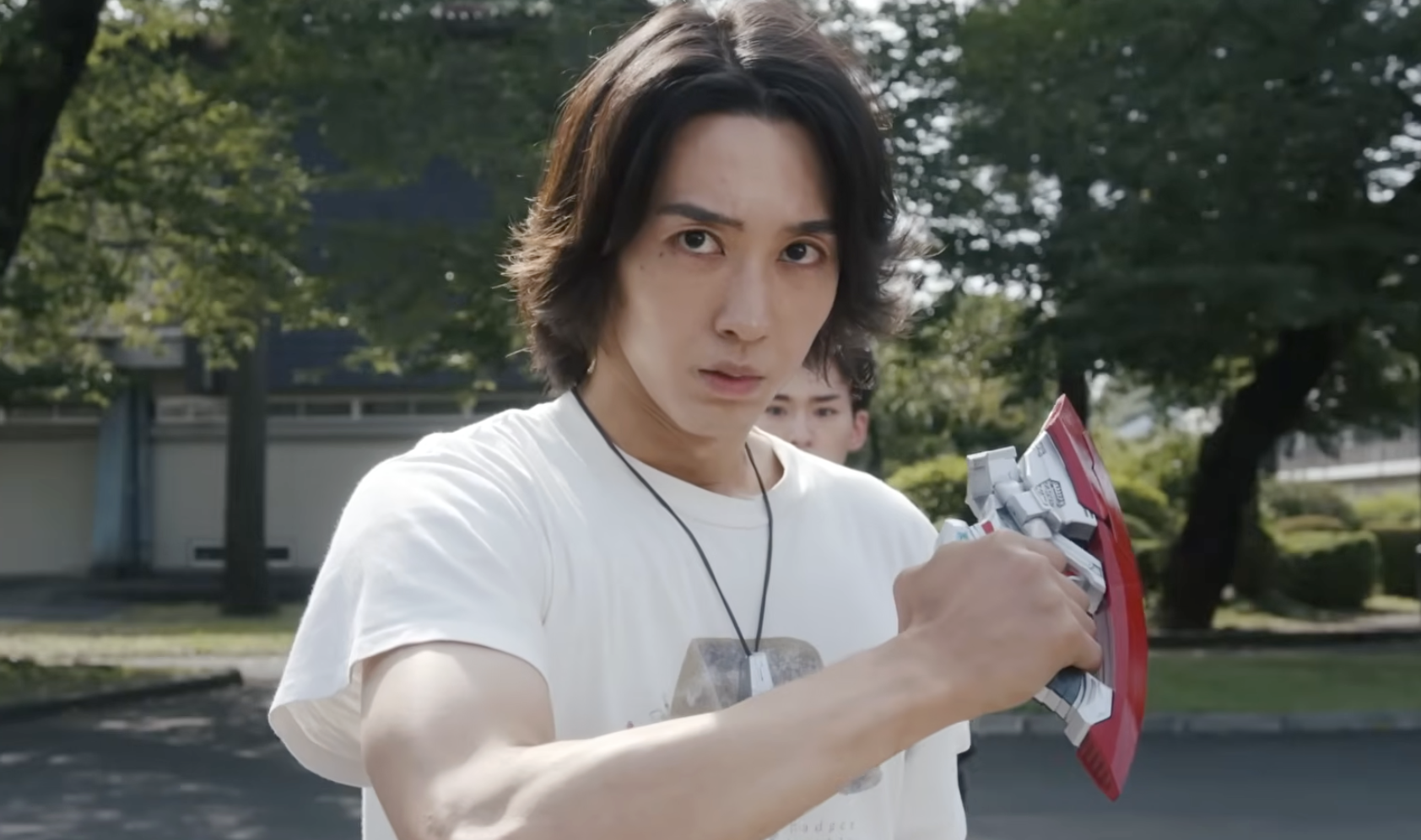

Those works targeted mainly children with appealing heroes and kaiju, whilst being high quality entertainment that expressed concepts that most couldn’t even imagine, surprising people and cultivating the power to dream and hope. To this day, the Ultraman series is still being produced, targeting the children and grandchildren of the generation who grew up watching Eiji’s final works. This work that can be passed down to touch the hearts of future generations is the cultivation of Eiji’s tireless persistence.

At the start of the 1960s, Eiji is quoted as having said “Computers will become human-like.” As he left this world in 1970, he was unable to experience the digital age. We now live in an age where CG has become the standard, and AI can easily make movies. It is indeed noteworthy that VES has now taken an interest in the Meiji era-born Eiji, who perfected cutting-edge analog techniques during his lifetime. Tsuburaya tokusatsu takes the maker’s will and gives it life, allowing the viewers’ imaginations to soar.